The Intricate Distinctions Between Eastern and Western Literature

What Sets Eastern Literary Works Apart From Western Ones?

March 11, 2022

Story Style & Structure

Let’s be honest—we as Americans have been raised to believe in the quintessential “happy ending.” Or, if the story is a tragic one, we try to extract light from the dark and find a positive takeaway. The star-crossed lovers will find a way to meet paths again at the end; the bullied schoolgirl finds respite from her harsh reality through creating art; the failed poet may lead a life devoid of prosperity, but the real fortune lies in the strength and insight he harnessed from his hardships. We want to believe that no matter the conflict, one will always find a means to overcome it. If it cannot be overcome, one will grow from it regardless. We rarely accept things as is.

In Eastern fiction, however, no one is safe from the whims of life. Many Asian stories are harrowing in nature and end tragically with no justification and no “inspirational” messages or insights to draw. Because life is sometimes just an unbridled sphere of cruelty and suffering. Nothing more, nothing less. I actually find that rawness to be more comforting than some of the over-saturated tropes Western fiction loves to tire.

Another thing is the difference in story structure. Eastern storylines may not centralize around an exact “man vs _____” conflict at all. While there may still be conflict presented, many stories are character-driven with an emphasis on emotions. Western storylines, on the other hand, are often heavy on conflict and inducing logos but are weak in evoking pathos. I’ll give an example below.

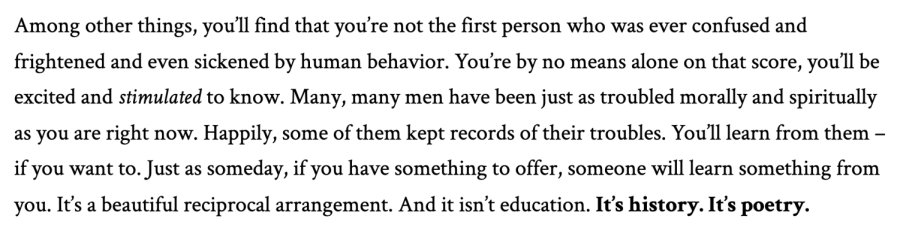

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger – Logos (Western)

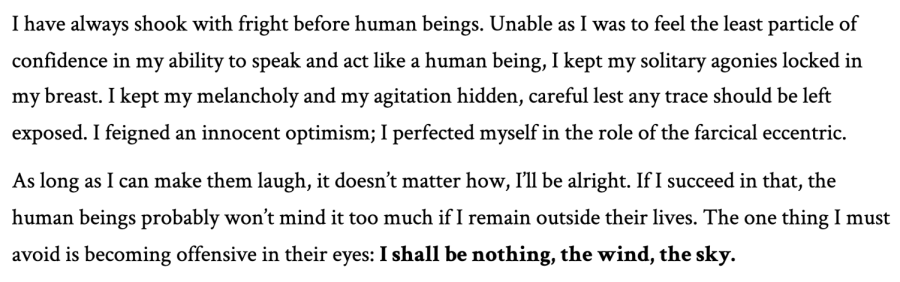

No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai – Pathos (Eastern)

Just those two ending lines alone embody the Western vs Eastern style quite nicely. Western writing likes to give you light at the end of the tunnel, something hopeful for you to cling onto while stimulating your brain. Eastern writing is as transparent and unalterable as “the wind, the sky.” There are times in which the dark will hold its power over the light, and the characters will express just that.

To think vs To feel

Much of Western literature aims to take us on an enlightening (or disheartening) intellectual journey. For instance, whenever I come across a passage or line that is undeniably substantial, I put my thinking cap on and try to dissect every facet of it. Alright, what’s the powerful life lesson I can get out of this? What’s the deep philosophical meaning here?

I feel like I have to squeeze as much meaning out of it as I can. Though sometimes I can barely squeeze any juice out of those metaphorical oranges, and I’d feel like I wasted my reading experience. But don’t get me wrong: I am forever grateful for the myriad of insight, socio-cultural awareness, and valuable life lessons I’ve gained from Western classical texts. For example:

1984 by George Orwell teaches you to think critically to define your own truth no matter how vehemently society or other external forces try to sway you otherwise.

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin paints a gutting portrait of the detriments produced by self-loathing, self-deceit, and internalized homophobia.

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov offers a playful and satirical take on the Soviet political climate.

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf addresses the injustices that women face in the creative field through an unapologetically feminist lens.

I could go on and on and on! I hold a lot of appreciation for Western literature’s richness in language and intellect—the way it opens your eyes and gets you to think, really think is so exciting—but I do feel dejected when I can’t get anything out of a work (and alas, I tread shamefully to its “Themes” section on SparkNotes).

Eastern literature serves a very different purpose, a refreshing one at that. Rather than getting the reader to think, it aims to make the reader feel. Japanese literature in particular has this dreamlike, lucid quality to it. I can’t quite capture it in technical terms, so I’ll try to get it across figuratively. I find it something akin to the sensation of wind.

Imagine a gust of wind flowing past you on a quiet summer evening. Except, no, you are not calculating its approximate speed and direction relative to the change in air pressure, nor are you speculating that rain might be on its way. You simply relish in the feeling, the way it careens against your skin and soothes you to the very core. And once it leaves, the contact it made with your soul—whether warm or cold—lingers on forevermore.

In Eastern writing, the character’s emotions are often brought to the forefront of the story grounds to evoke a deep, visceral response. It is like putting a picture frame around a feeling. I’ve provided a few examples below:

秋の暈 ( Autumn Halo by Oda Sakunosuke )

れっちまった悲しみに ( “Upon the Tainted Sorrow” by Chūya Nakahara )

こゝろ ( Kokoro by Natsume Sōseki )

大導寺信輔の半生 ( “Daidoji Shinsuke: The Early Years” from Rashōmon and Seventeen Other Stories by Akutagawa Ryūnosuke )

“Were it not for shadows there would be no beauty.”

It is evident that Eastern writing often does not illustrate the light among the darks. There is actually an essay written by Japanese literary giant Junichirō Tanizaki that explores such aesthetics. Written in 1993, In Praise of Shadows examines the nuances in Japanese and Chinese architecture, jade, food, and even toilets, and how its lack of luster contrasts from the Western delight in shine. As the title suggests, Tanizaki argues that beauty can all the well be found in the dark, the unlit, as long as we make an effort to look past the light.

“We find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates.

A phosphorescent jewel gives off its glow and color in the dark and loses its beauty in the light of day. Were it not for shadows, there would be no beauty.”

There is an inherent cultural polarity between Western and Eastern aesthetics. The inclination towards flashiness and idealistic need for structure, perfection, and expansion are concepts that are purely Western. Think—the modern conception of the “American Dream” and the historical notion of “Manifest Destiny.”

“But the progressive Westerner is determined always to better his lot. From candle to oil lamp, oil lamp to gaslight, gaslight to electric light—his quest for a brighter light never ceases, he spares no pains to eradicate even the minutest shadow.”

I’ve mentioned earlier that Westerners struggle to accept things as they are. We want to believe in the “happily ever after”, and if the hero dies, then there must be some bigger lesson to take away. Conversely, Eastern aesthetics are deeply rooted in the present moment, encompassing all its rawness and imperfections. This sense of transparency lies at the heart of many Eastern literary works. It does not have to be polished and tied together with a smile to be moving. It does not have to shine to be beautiful.

“We Orientals tend to seek our satisfactions in whatever surroundings we happen to find ourselves, to content ourselves with things as they are; and so darkness causes us no discontent, we resign ourselves to it as inevitable. If light is scarce then light is scarce; we will immerse ourselves in the darkness and there discover its own particular beauty.”