The Untold Story of Titanic’s Forgotten Chinese Survivors

All 706 survivors of the Titanic disaster were claimed—all except for six Chinese men who were turned away and seemingly erased from history. Who were they? Why was their story never told?

I’ve been enthralled by the Titanic ever since I watched the love story of Jack and Rose unfold on a big movie screen when I was a little kid. My parents took me to see James Cameron’s Titanic to help us “assimilate” after just moving from China. I remember with stark clarity the night I walked into the movie theater as a scared, lonely kid in a new country, and I walked out still a scared, lonely kid but with something to dream about.

The film ignited in me a fervid fascination with the history of the Titanic—one that would catapult me into a deep-seated, unwavering love for stories. Since that night, I’ve spent my whole life chasing them. Tragic ones. Heroic ones. Untold ones.

Delightfully, the Titanic is chock-full of them. The ship’s plight was entangled with many evocative passenger stories: the band that played until their dying breath; the heroic efforts of “The Unsinkable Molly Brown“; the drunk baker who survived for two hours in freezing waters by chugging alcohol before the sinking.

Despite the Titanic now decaying in a watery grave 12,500 deep on the ocean floor, her stories will never perish, having been immortalized in countless books, documentaries, and museums. There is, however, one story that seems to have slipped into history’s shadows: the six Chinese passengers who miraculously survived—and vanished in a flash.

The Story of the Six

On April 10th, 1912, the RMS Titanic set sail on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England to New York City. Tragically, the ship struck an iceberg and sank on the night of April 14th, taking the lives of 1,500 out of its 2,229 passengers and crew.

There were eight Chinese passengers who boarded the ill-fated ship. They all worked together as sailors in Britain, but because of an ongoing coal strike there at the time, their company had to transfer them to work in North America.

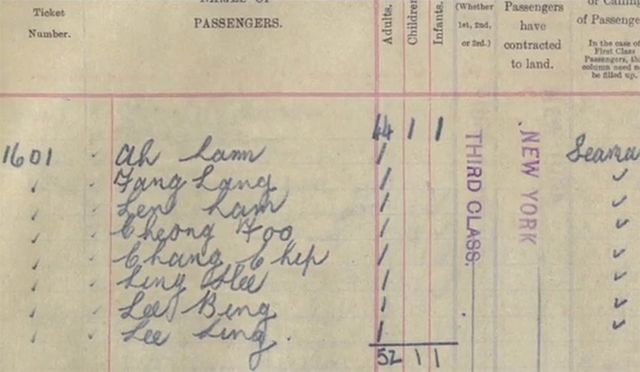

Among the Chinese passengers, a remarkable six survived: Lee Bing, Chang Chip, Ling Hee, Ali Lam, Chong Foo, and Fang Lang.

Lee Bing, Chang Chip, Ling Hee, and Ali Lam boarded a folding lifeboat together. Chong Foo got on the last lifeboat, just before the Titanic sank completely. The last survivor, Fang Lang clung to a wooden door and floated on open water before he was rescued from the icy Atlantic waters.

Surely, we all know the infamous door scene in James Cameron’s Titanic—one that has sparked a decade’s worth of debates over “Could Jack have fit on the door?” What many do not know is that this scene was inspired by the real-life rescue of Fang Lang.

In fact, the blockbuster has a deleted scene depicting the rescue of a Chinese man clinging to a piece of wood.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpItxVftA60

After the sinking

Even after the Carpathia arrived to rescue victims on April 18, 1912, the miraculous survival of the six Chinese men did not bring an end to their troubles. Every Titanic survivor was allowed entry into the United States without question and given aid and medical relief. But not the Chinese. They were sent away within 24 hours of arriving in New York, simply on the basis of race.

After landing on Ellis Island, New York, they were expelled from the country because of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, an anti-immigration law that barred Chinese immigrants from entering the US. Shunned, the six were sent to Cuba and vanished without a trace.

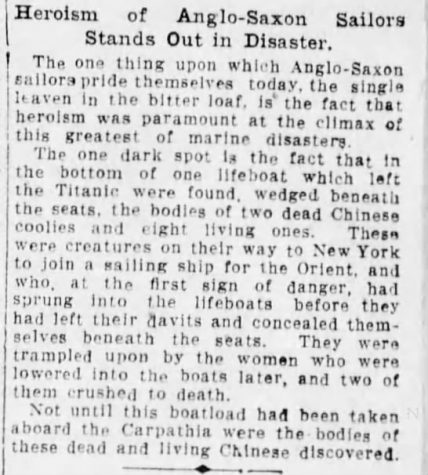

Newspapers of the time vilified the Chinese men as cowards who had survived by hiding under seats. In a report filed days after the sinking, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle branded them as “creatures” who “at the first sight of danger, had sprung into the lifeboats” and “concealed themselves beneath the seats.” They were dehumanized and shamed for living at the expense of women and children, while their white counterparts were praised for their bravery.

It was indisputable how racism contorted the narrative of their survival, robbing them of their rightful place in the Titanic tale.

Within Chinese culture, being shamed is considered a fate worse than death; many of these survivors did not tell their stories to their families in fear of bringing dishonor, another reason so little is known about these men. Even their own descendants, who have recently been traced down, were left in the dark about their tragic fable.

The six men seemingly disappeared from history—until now. A documentary film directed by Arthur Jones with executive director James Cameron, The Six, shines a spotlight on their lost story over a century after the doomed voyage.

The documentary uncovers a tale beyond the Titanic, a story sewn by the racial discrimination and xenophobia that closely echoes today’s America.

Anti-Asian sentiment in the past and present

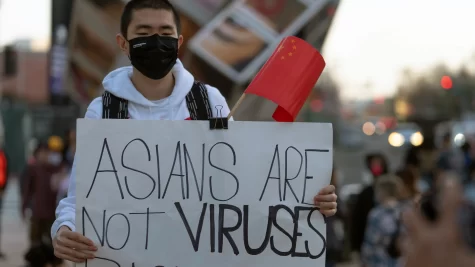

Just as the six Chinese survivors were scapegoated for living at the expense of other victims, America’s pandemic-age Asians were brutally blamed and targeted for the spread of the virus. Former President Donald Trump’s use of racist terms like “China Virus” and news outlets’ reinforcement of the label fueled the fire that blazed into a countrywide spike in anti-Asian hate crime.

Asian Americans were physically attacked, verbally harassed, spat upon, and subjected to racial slurs. According to Stop AAPI Hate, an organization tracking instances of violence and verbal abuse against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, there were more than 10,900 incidents reported between March 2020 and December 2021. Anti-Asian harassment soared in 2020 and 2021, with The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism revealing that anti-Asian hate crime had increased by 339 percent last year compared to the year before.

In March 2021, the devastation of the Atlanta shootings compelled many Asian Americans to speak out in a new way. In the weeks that followed, rallies erupted across the entire country, with hundreds of thousands of people launching petitions and crowdfunding efforts to support victims and condemn anti-Asian violence. The #StopAsianHate movement took off on every social media imaginable, taking center stage in the American social sphere.

In the ashes of modern American history, there lies the Chinese massacre of 1871, when a mob in Los Angeles’ Chinatown attacked and murdered 19 Chinese residents in cold blood. Anti-Asian sentiment reached its climax a decade later with the crippling Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

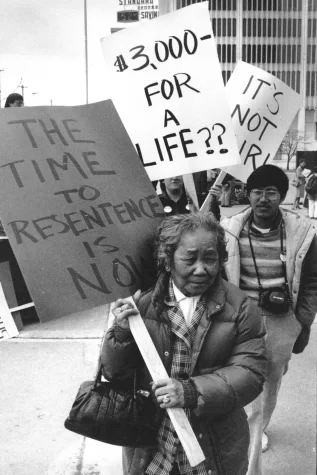

World War II saw the forced internment of about 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast (an estimated 62 percent of whom were U.S. citizens) in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the Vietnam War, refugees from Southeast Asia faced routine discrimination and hate, including attacks by Ku Klux Klan members on shrimpers in Texas. And in 1982, Vincent Chin, a Chinese American, was beaten to death by two Detroit autoworkers who thought he was Japanese. The killing took place during a recession that was partly blamed on the rise of the Japanese auto industry.

It is important, especially now, to open your eyes to stories such as these six Chinese survivors that were rendered invisible by the tendrils of racism and xenophobia. Hear their voices. Wipe away the ashes. Because if we do not learn about history—even the cruelest and bloodiest—we are doomed to repeat it.