Unearthing Black Voices: Four Remarkable Figures You Didn’t Learn in History Class

February marks Black History Month in the United States, a time for remembrance and reflection as the country reminds itself of its bloodstained racial legacy. And so, it’s also a time to honor the achievements and contributions of the Black figures who dared to rewrite it—or write their own despite it.

Names of pioneers such as Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman often light up the headlines and the textbooks, and while they wholly deserve their places in the spotlight—what about those hidden away in the shadows, making their own ripples from beneath the surface? This month is dedicated to unearthing all the voices and stories that helped transform our society and history, even the ones who were forgotten or sidelined by the masses. Here are five trailblazing yet overlooked Black Americans who deserve equal credit for their legacies.

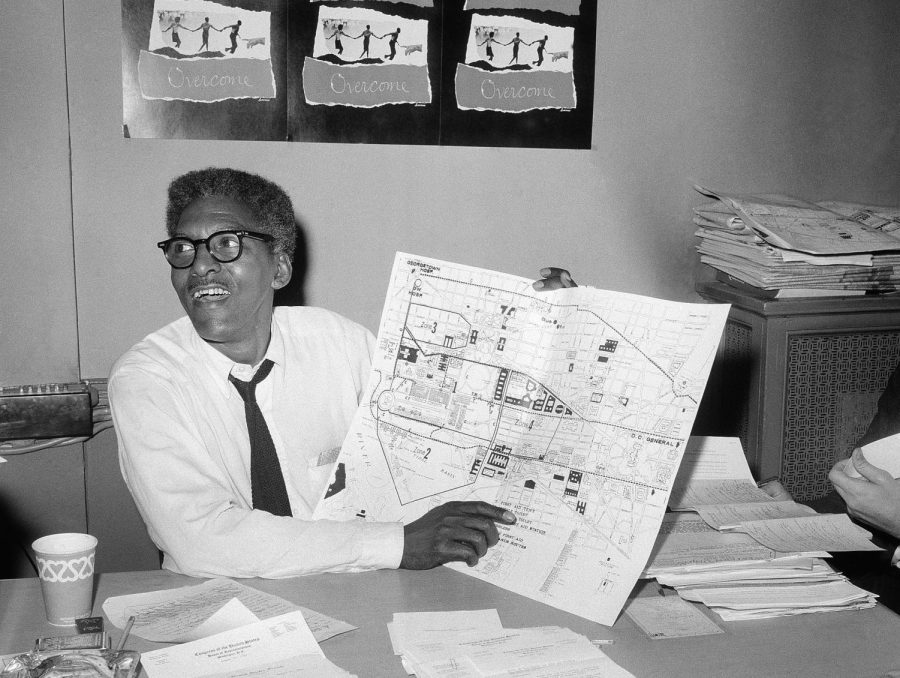

BAYARD RUSTIN, the openly gay strategist behind MLK’s practice of nonviolent civil resistance (1912-1987)

While there is no American child foreign to the words “I have a dream”—few, if not all, are acquainted the mastermind behind it all. Bayard Rustin was a gay civil rights activist who served as a close advisor of Martin Luther King Jr as well as a strategist and organizer for various protests/public demonstrations during the Civil Rights Movement. However, his orientation put him at odds with the cultural norms of the larger society and pushed out of the public domain, leaving him to work behind the scenes.

Rustin contributed to a hugely influential essay pamphlet on alternate non-violent approaches, which would shape the emergence of new, peaceful protest tactics going forward. Furthermore, it was Rustin who convinced King to employ the nonviolent approach that became so synonymous with his politics. This strategy on Rustin’s part–a deliberate means to dissociate Black people from any form of violence that could (and would) be used against them–paved the way for monumental change.

Most notably, Rustin was a key organizer of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, at which King delivered his legendary “I Have a Dream” speech on August 28, 1963. Years later, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Rustin’s talents and tireless activism were transferred to human rights and the gay rights movement. Though he was trialed multiple times and twice went to jail for his civil disobedience homosexuality, he continued to fight for equality. In the 1970s and 1980s Rustin worked as a human rights and election monitor for Freedom House and also testified on behalf of New York State’s Gay Rights Bill.

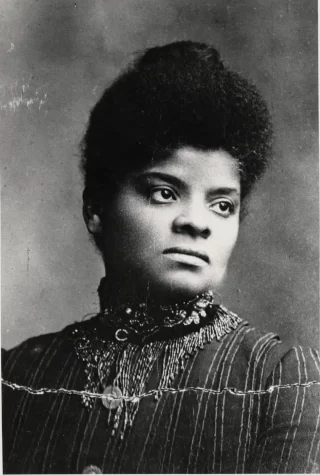

IDA B. WELLS, an anti-lynching activist who paved the way for investigative journalism (1862-1931)

In a time of rampant racism and yellow journalism, documenting and speaking the truth about lynchings in the South was a rare and dangerous act. That, however, did not stop journalist Ida B. Wells. When one of her friends was lynched in Memphis, Tennessee in 1892, she decided she could not let the defamation and murder of African American men stand any longer.

For months, Wells traveled throughout the South investigating lynchings. Wells documented an average of two hundred lynchings every year in the United States; she used eyewitness interviews, testimony from families, and looked through records. The New York Times in its recent obituary for Wells noted, “She pioneered reporting techniques that remain central tenets of modern journalism.”

Forcing her audience to deal with the fact that many lynchings were grounded in hearsay and not evidence, she was able to force those who might be apathetic to the plight of many Black Americans in the South to see that in many cases, “men have been put to death whose innocence was afterward established.” In a world where a Black man could be murdered with nothing but rumors supporting his guilt, Wells refused to operate her own claims on similar errors. She rose above.

On top of fighting racial injustice, she remained active in the women’s rights movement, starting the Alpha Suffrage Club, the first suffrage association for Black women in the country. Wells established it in response to Black women being denied entry into the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA), with the intention of giving Black women a voice in white/male-dominated political spaces.

MARSHA P. JOHNSON, unapologetic transgender activist and catalyst for the LGBTQ movement (1945-1992)

A pioneer for the LGBTQ community–bold, courageous and outspoken–Marsha wore her makeup and dresses with pride, and campaigned valiantly to support better rights for trans people, having experienced social ostracization and homelessness because of her own identity.

Despite describing herself as a “nobody, from Nowheresville,” she would become a catalyst for the modern LGBTQ movement when she fought on the front lines in an uprising against police violence, in what become known as the Stonewall Riots in 1969. The first anniversary of the protests prompted the first gay pride parade in 1970.

In 1972, Marsha went on to launch the group Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries with fellow activist Sylvia Rivera to offer houses to homeless transgender youth and sex workers. They created the first LGBT youth shelter in North America and the first organization in the United States led by trans women of color, according to the Global Network of Sex Work Projects.

Through the work of STAR, Marsha not only gave the marginalized the means of survival, but she also brought dignity to their lives, caring for each person she encountered. Her warm, generous personality is remembered by the people whose lives she touched, many calling her a ‘saint’. Marsha’s embodiment of saintly love attracted many to her life, changing the way she was perceived as a trans woman, and expanding her audience for her works in the trans rights movement. Marsha was also a founding member of Gay Liberation Front—a movement fighting for LGBTQ rights in the US—and she worked as an AIDS activist in the 1980s.

DAVID RUGGLES, first Black bookstore owner and full-time abolitionist (1810-1849)

The country’s first Black-owned bookstore opened in New York City in 1834, the creation of David Ruggles. He was an abolitionist, founder and writer of the anti-slavery newspaper Mirror of Liberty, and one of the early organizers of a network that would become the Underground Railroad. Everything about his work, including his bookstore, was done to support and fight for Black lives.

In 1825, Ruggles began working for abolitionist newspaper The Emancipator as a traveling salesman and speaker. He used these trips “to urge Negroes to support the anti-slavery press and better their own economic, cultural and social condition, [and] he used them also to begin his fight against the colonization movement and for equal rights for the Negro.”

Ruggles continued this message by opening his own bookstore, stocked with abolitionist and feminist publications. He later expanded to include a reading room and lending library, as most of the city’s literary hubs excluded Black people. Although there was a joiner’s fee, Ruggles’ reading room was free to city visitors, a nod that it was safe for those escaping slavery. One such visitor was Frederick Douglass, whom Ruggles took in, hiding him for several days before sending him with money and letters of introduction to fellow abolitionists in New Bedford.

It was estimated that Ruggles helped 600-1000 men and women to escape from slavery. His bookstore was much more than a literary space—these books were providing the knowledge to support and strengthen the abolitionist movement.

Sources:

https://www.history.com/news/bayard-rustin-march-on-washington-openly-gay-mlk

https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/ida-b-wells

https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/2021/09/02/david-ruggles-first-black-bookstore-owner-antislavery-abolitionist-journalist-printer/8158701002/

https://wams.nyhistory.org/growth-and-turmoil/growing-tensions/marsha-p-johnson/