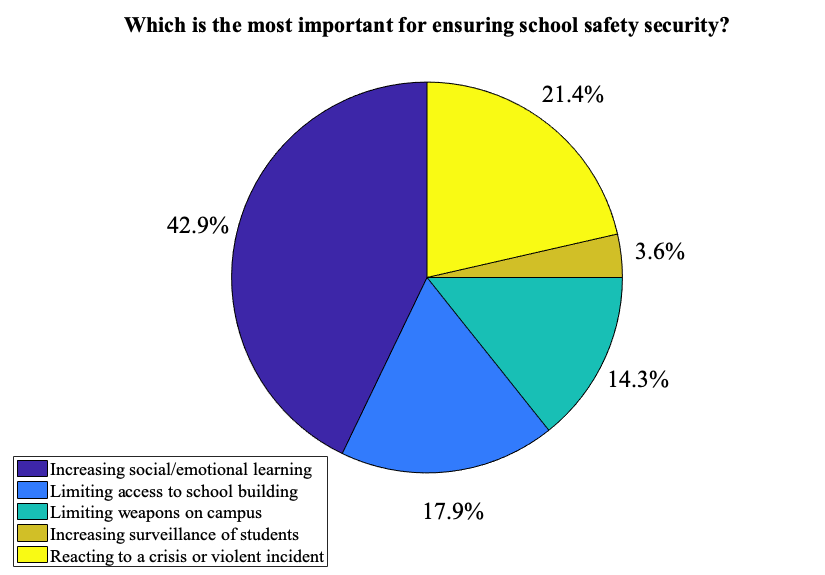

With the recent surge in school shootings, districts across the nation are implementing a battery of safety measures to combat catastrophes in emergency situations. Inherent to these new systems designed for our protection is the controversy regarding which approaches are successful and which divert resources away from the source of the problem. While it is challenging, if not impossible, to accurately assess the efficacy of a particular approach, a growing body of research suggests the importance of preventative strategies, specifically those that target social and emotional welfare, outweighs that of physical security measures.

In the Great Neck school district, money has practically been poured into funding for physical precautionary measures. Most recently, the 2018-2019 budget allocated approximately $1.5 million from the district’s capital reserves and fund balance to strengthen security at the main entrances of all district facilities. In the span of several months, North and South have been equipped with double-door security vestibules, electronic locks, an intercom buzzer system, additional security cameras, and a secure pass-through for drop-off items. Village School, following close behind, has now granted students IDs which serve as keys for unlocking the school doors.

While the district has done an exceptional job of prioritizing student safety, the disproportionate focus on measures targeting surveillance and limiting building access may be creating an increasingly negative environment. When students walk the halls and have security guards watch their every step, they may begin to wonder where the line is drawn between student freedom and what may be simply a facade of safety. Primarily when profiling due to one’s ethnicity, gender or other bias-inducing factors comes into play, some measures may have the opposite effect of what is intended. Studies have suggested that heightened security measures create increased victimization and disruption at school and even foster student resentment (Hyman & Perone, 1998; Schreck, Miller, and Gibson, 2003). Programs aimed at improving student’s ability to build positive relationships and express feelings in nonviolent ways have a considerably lower tradeoff between hypothetical success and their impact on school climate, as they encroach upon student privacy and comfort to a lesser extent.

There is no doubt that physical security measures are essential in any multi-tiered system of defense. However, the question then becomes to which tiers we give more value. Increased surveillance of students and limited access to the campus may equip us to handle emergency situations, but will they do anything to address the source of the violence? In a 2004 report, the U.S. Secret Service and the U.S. Department of Education found that “almost three-quarters of the (school shooting) attackers felt persecuted, bullied, threatened, attacked, or injured by others prior to the incident.” Even with the district’s provision of mental health services and more vigilant stance on matters of bullying and discrimination, there is still more that can be done to integrate social-emotional learning into our curriculum. According to the Aspen Institute, “Social and emotional development is the process through which people acquire and apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.” Students who learn to resolve their differences with words are unlikely to become adults who use violence to solve their problems. Extensive research has supported this finding, with lessons in confidence and emotional resilience resulting in higher levels of social-emotional competence, a reduction in problem behaviors (hostility, substance abuse, nonattendance, etc.), and even improved academic achievement (Greenberg, et al., 2003; Ashdown & Bernard, 2011; Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011; Bar-On, 2012).

With the widespread stigma around mental health, there is a need to create school environments that understand, legitimize, and foster mental health supports for all students’ well-being. School staff can play a critical role in promoting student connectedness through positive relationships with students and the provision of appropriate mental health supports. Teachers can reinforce anti-bullying interventions in their classrooms, encourage the use of relaxation strategies for a student working on anxiety management, and provide regular feedback to mental health professionals regarding the academic and behavioral progress of students in their classroom. At other times, they may have to expand their role by seeking additional training from other mental health professionals when students present more intensive needs. They need to learn and be proficient in teaching problem solving and coping skills that can benefit all students.

All in all, the lack of education in social and emotional intelligence among teachers, administrations, and students has proven fatal. Not only will training in such areas reduce the risk of violence, but it will improve stress management, emotional self-awareness, empathy, and interpersonal relationships. It is not enough to host assemblies once a month on the importance of mental health or to have guest speakers inform us of the perils of bullying once a year. We need a long-term plan. If the school administration begins to incorporate aspects of social and emotional education into the classroom, we can prepare each student to live a successful, non-violent life.

Literature Cited

Ashdown, D. M., & Bernard, M. E. (2011). Can Explicit Instruction in Social and Emotional Learning Skills Benefit the Social-Emotional Development, Well-being, and Academic Achievement of Young Children? Early Childhood Education Journal, 39(6), 397-405. doi:10.1007/s10643-011-0481-x

Bar-On, R. (2012). The Impact of Emotional Intelligence on Health and Wellbeing. Emotional Intelligence – New Perspectives and Applications. doi:10.5772/32468

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405-432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Greenberg, M. T., Weissberg, R. P., Obrien, M. U., Zins, J. E., Fredericks, L., Resnik, H., & Elias, M. J. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist, 58(6-7), 466-474. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.466

Hyman, I. A., & Perone, D. C. (1998). The Other Side of School Violence. Journal of School Psychology, 36(1), 7-27. doi:10.1016/s0022-4405(97)87007-0

Schreck, C. J., Miller, J. M., & Gibson, C. L. (2003). Trouble in the School Yard: A Study of the Risk Factors of Victimization at School. Crime & Delinquency, 49(3), 460-484. doi:10.1177/0011128703049003006

Vossekuil, B. (2002). The final report and findings of the Safe school initiative: Implications for the prevention of school attacks in the United States. Washington, D.C.: The Service.